The Great AI Money-Go-Round: Is the Boom Eating Itself?

The artificial intelligence sector is currently defined by staggering numbers: multi-billion dollar investments, sky-high valuations, and an insatiable demand for computing power. Tech giants are pouring capital into promising AI startups, and chipmakers like Nvidia have seen their market caps soar to astronomical heights. But beneath the surface of this explosive growth, a complex and potentially troubling economic pattern has emerged, leading analysts and investors to ask a critical question: Is the AI boom building a revolutionary future, or is it just eating itself?

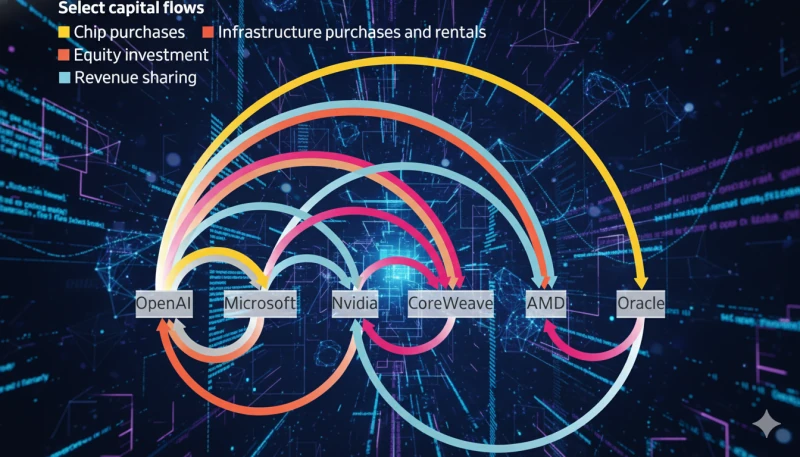

This phenomenon, dubbed "circular financing," describes a feedback loop where the money being invested into AI doesn't just fuel innovation—it flows directly back to the investors themselves, creating a dizzying money-go-round that could be artificially inflating the entire industry. Understanding this mechanism is key to separating sustainable growth from speculative hype.

How the AI Money-Go-Round Works

At its core, the circular financing model is straightforward. It works like this:

- Massive Investment: A tech giant, like Microsoft or Amazon, invests billions of dollars into a leading AI startup, such as OpenAI or Anthropic.

- Essential Purchases: To build and train their sophisticated models, these AI startups require enormous amounts of computational power. They spend a huge portion of their newly acquired investment capital on cloud computing services and specialized AI chips.

- Revenue Loop: The startups purchase these essential resources from the very same tech giants who invested in them (e.g., OpenAI paying Microsoft for Azure cloud services) or from chipmakers who are also major investors in the ecosystem.

This cycle creates a self-reinforcing loop. The tech giant's investment becomes the startup's expenditure, which then becomes the tech giant's revenue. On paper, the cloud division's earnings look phenomenal, and the chipmaker's sales go through the roof, justifying their own soaring valuations.

The Bear Case: An Artificially Inflated Bubble?

Critics of this model argue that it creates a distorted picture of the AI economy, raising several red flags that echo previous tech bubbles, like the dot-com crash.

The primary concern is the inflation of revenues and valuations, a mechanism made extraordinarily profitable by the massive multiples at which tech firms are valued. When a significant portion of a company's revenue growth comes from customers spending the investor's own money, it's not organic growth; it's a closed loop. However, in a market that values a company at 20 or 30 times its revenue, an extra $100 million in sales—even if it's recycled capital—can add billions to a firm's market capitalization. This inflated valuation can then be leveraged to borrow even more money, creating a powerful incentive to keep the cycle going.

Furthermore, this system creates immense barriers to entry. The cost of the computational power required to compete at the highest level is prohibitive for startups without a multi-billion dollar partnership with a hyperscaler. This concentrates power in the hands of a few dominant players, stifling competition from smaller, independent innovators.

The Bull Case: A Necessary Foundation for a New Era?

On the other hand, defenders argue that this is not a speculative bubble but a pragmatic and necessary way to finance a technological revolution. The AI cycle, they contend, is fundamentally different from the dot-com era.

The core of their argument is that AI development is incredibly capital-intensive. The need for massive data centers and millions of specialized chips is not an artificial demand; it's the real, unavoidable cost of building foundational technology. The tech giants are the only entities with the infrastructure and capital to support this level of development at scale. From this perspective, these circular arrangements are less about financial engineering and more about deep, strategic partnerships.

Proponents also point to the fact that, unlike many dot-com era companies, today's AI leaders are generating substantial and rapidly growing revenue from real enterprise customers. The spending is driven by tangible productivity gains, leading to durable contracts for software and services. While the circular flow is real, it's happening alongside genuine, accelerating demand from the wider market.

Conclusion: Symbiosis with a Side of Hype

The truth about the AI boom likely lies somewhere between the two extremes. The circular financing model is neither a pure accounting trick nor a perfect, symbiotic partnership. It is a novel and complex economic engine driving one of the most significant technological shifts in history, and it comes with both incredible potential and inherent risks.

Ultimately, the test will be one of monetization and market expansion. The key indicator to watch is the growth of real, external revenue from a diverse customer base. Can the AI startups, currently nurtured by their hyperscale investors, eventually generate enough independent profit to stand on their own and justify their multi-billion dollar price tags? If they can, this period will be remembered as a necessary, if unusual, incubation phase. If not, the great AI money-go-round will slow down, and the industry will face a correction that could be felt far beyond Silicon Valley.